Serverless vs. Containers

August 17, 2018

We live in exciting and worrying times.

In serverless and containers, we have two amazing technologies that provide productive, machine-agnostic abstractions for engineers to work with. And yet, there seems to be an unbridgeable chasm between the two camps.

If you have read anything I wrote in the last two years, you know that I am firmly in the serverless camp. But I was also an early adopter of containers. My first containerization project came in early 2015, shortly after Docker reached the 1.0 milestone.

This post is not another attempt at stoking the fire in the ongoing tribal warfare or to proclaim victory for either camp. Instead, I will attempt to take an objective look at the state of serverless and containers, the tradeoffs they offer and give my honest view on what the future holds.

Given that serverless and function-as-a-service (FAAS) are often used interchangeably already, for the purpose of this article I will restrict the definition of serverless to mean FAAS offerings such as AWS Lambda.

State of Containers

Things have come a long way since the early days of Docker. A rich ecosystem of tools has spawned up to meet our needs as we run increasingly complex systems on containers.

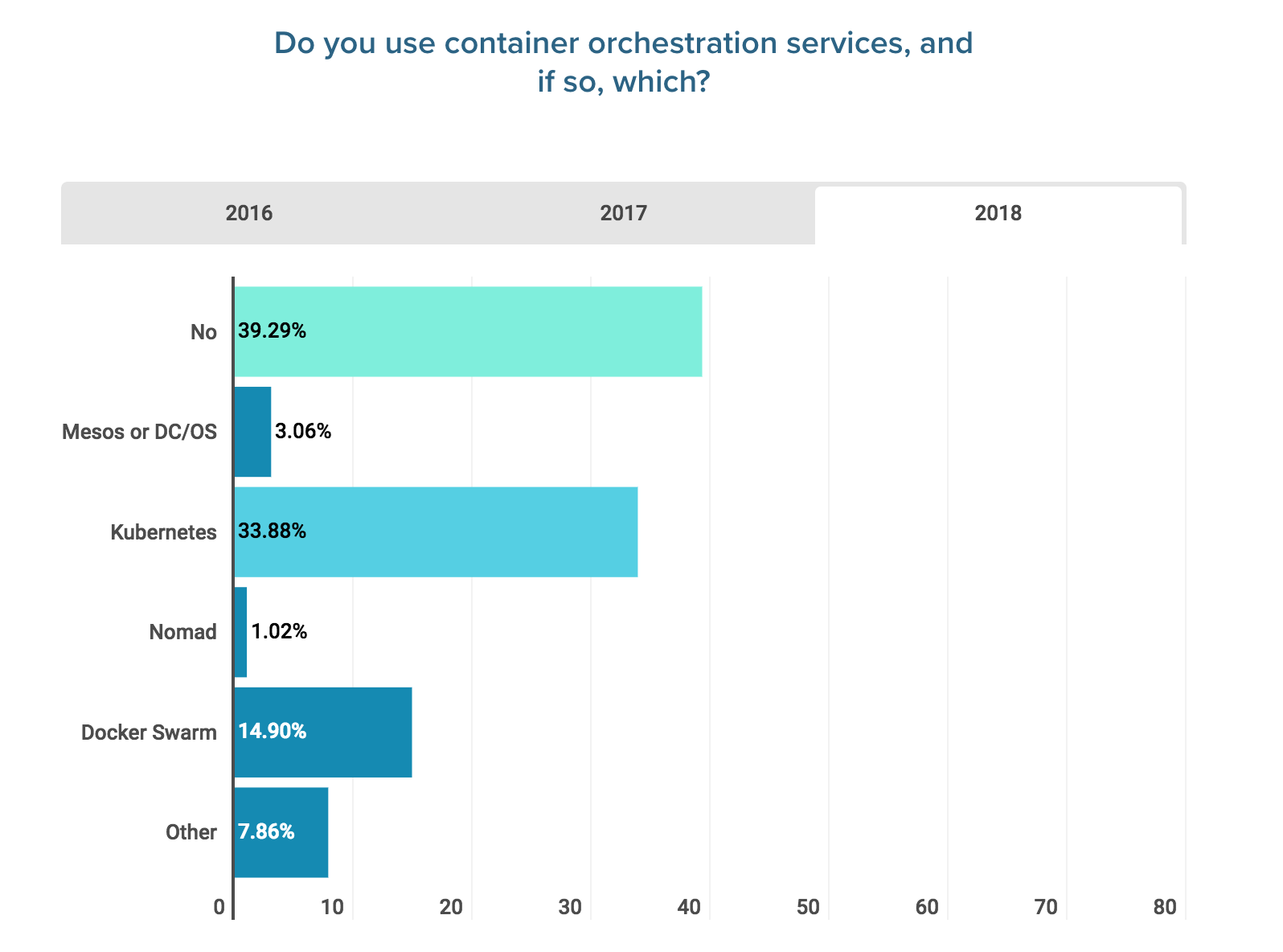

Kubernetes absolutely dominates the container orchestration space, as is reflected in Logz.io’s DevOps Pulse survey in 2018.

It’s testament to Kubernetes’ market dominance that AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure all offer managed Kubernetes as a service, in the form of EKS, GKE, and AKS respectively.

AWS also has its own managed container service, ECS. Which provides tighter integration with the rest of the AWS ecosystem.

Looking further afield, AWS Fargate became generally available in 2018 and lets you run containers without having to manage servers; hence blurring the line between containers and serverless.

Service meshes such as Istio and Linkerd are also gaining visibility and adoption. They move common cross-cutting concerns such as tracing and circuit breakers out of the application layer. By addressing these concerns in the infrastructure layer, they provide a language and runtime agnostic solution to these challenges. This makes them a great fit for the modern IT organization, that is building microservices using a variety of different languages.

State of Serverless

Whilst the hype around serverless has not been around for as long as containers. It’s worth remembering that AWS Lambda was announced at re:invent 2014, only a month after Docker reached 1.0. It shipped with basic logging and monitoring support with CloudWatch, even though many of the event sources we now rely on, such as API Gateway, were introduced afterwards.

Since then, Google Cloud, Azure, and IBM have all followed suit in announcing their own serverless offerings to compete with Lambda. According to a survey conducted by the CNCF, AWS Lambda is the clear market header and owns 70% of the market.

Aside from these managed services, there are also solutions that let you run serverless on your own Kubernetes cluster. These include the likes of Kubeless and the newly announced Knative from Google and co. Whilst it’s great that these solutions are attempting to meet many developers where they are, I can’t help but feel that they forfeit the best thing about serverless—not having to worry about servers!

Adoption Trends

Adoption for both serverless and containers are growing at a rapid rate, according to several surveys and studies. Here are some of the highlights I picked out.

- A study by Cloudability found that container adoption amongst AWS users grew 246% during Q4 2017, up from 206% in Q3. Meanwhile, the same study found that serverless adoption by AWS users grew 667% in Q4 2017, up from 321% in Q3.

- A recent survey by Serverless Inc. found that 82% of correspondents use serverless at work in 2018, up from 45% in 2017. And over 53.2% said their use of serverless technologies are critical for their job.

- The Serverless Inc. survey also reports that 24% of correspondents had limited or zero experience with public clouds before adopting serverless. And that 20.2% of correspondents worked for large enterprises with over 1000 employees.

- Logz.io’s DevOps Pulse survey found that 60.71% of correspondents have adopted container orchestration in 2018, up from 42.11% in 2017.

Interestingly, the DevOps Pulse survey reports a much smaller increase in serverless adoption than other reports. Up from 30.55% (2017) to 42.58% in 2018. This is perhaps correlated with the distribution of its correspondents. Where 28.54% identified themselves as developers vs. 44.26% that identified as DevOps, DevSecOps, SysAdmin, or SRE.

This is in keeping with my experience with the aforementioned chasm between the containers and serverless camp. Where those that identify themselves as developers are more likely to prefer serverless, and those that identify as DevOps are more likely to go with containers.

Control vs. Responsibility

Debate about serverless vs. containers often starts with control, or the lack thereof in the case of serverless. This is not new. In fact, I clearly remember the same debates around control when AWS was starting to gain traction way back in 2009. Now 10 years later, the dust has settled on that original debate but we have failed to learn our lesson.

It’s human nature to want control, but how much are you willing to pay for it? Do you know the total cost of ownership (TCO) you will take on?

The ability to control your own infrastructure comes with a lot of responsibilities. To take on these responsibilities, you need to have the relevant skill sets in your organization. That means salaries (easily the biggest expense in most organizations), agency fees, and taking time away from your engineers and managers for recruitment and onboarding.

Given the TCO involved, the goal of having that control has to be to optimize for something (for example, to achieve predictable performance for a business critical workflow), and not having control for its own sake.

It takes significant engineering know-how and investment to build a container-based, general purpose compute platform that is as efficient, scalable, and resilient as a serverless offering such as AWS Lambda. Most organizations are simply not equipped to pull this off. I have known a few large enterprises that have failed miserably in their attempts, despite vast investments of time and money.

Tooling Support

With serverless you get the basic observability tools out of the box—logging, metrics, and tracing. Although there are caveats with these, they are generally sufficient as you start out.

CloudWatch Logs for instance, is severely limited by its inability to search across multiple log streams. However, you can easily stream the logs from CloudWatch to a log aggregation service such as Logz.io using a Lambda function or through a Kinesis stream first.

Vendors who have traditionally catered for the IAAS or container market are starting to offer support for serverless applications as well. However, they need to adapt their approach as the agent-based approach is no longer possible with serverless.

There is also a growing number of vendors who are focused on solving observability and security problems for serverless applications. However, most are still in the early stages of development and are not yet ready for serious production use.

Compared to serverless, the container space has a more mature and diverse ecosystem of tools. In fact, one of the challenges I find working with containers is to deal with the overwhelming number of choices!

With ample opportunity for tinkering, I also find that teams can lose sight of the prize (i.e. building a better product for our customers) and fall into the trap of over-engineering.

Tooling support for serverless is getting better all the time, but for the time being at least, we are still a long way behind containers. The challenge for those working in the container space is to fight the urge to tinker and strive for simplicity.

Vendor Lock-In: Risk vs. Reward

Detractors of serverless often use vendor lock-in as their argument. At the same time, most AWS customers are actually asking for tighter integration so they can extract even more value from the platform.

Vendor lock-in is a risk, sure. But as any investor will tell you, you’d never make any money if you don’t take on risks. The trick is to take calculated risks that give you the best return.

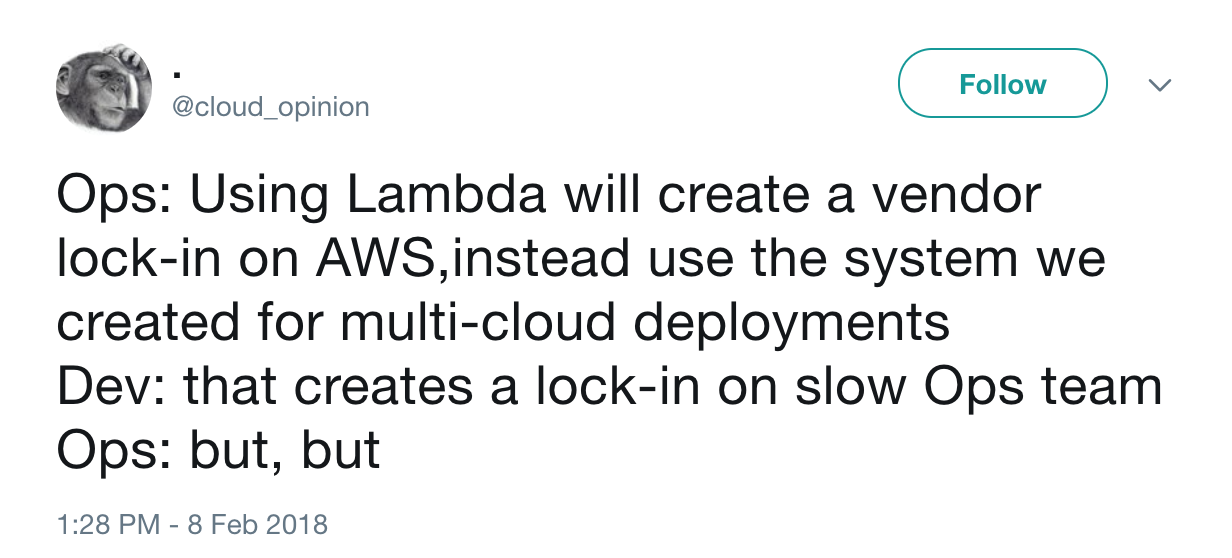

For all the attention that it has received, vendor lock-in is a danger that has come to pass for a precious few. Instead, you are far more likely to find over-engineered solutions to prevent vendor lock-in that instead create other forms of lock-in, be it with internal teams or with other private cloud vendors.

Again, this is not new. We had this same debate with ORMs years ago. We created all these abstractions to prevent vendor lock-in, except the risk never materialized into problems for most of us. All that happened was that we spent a lot of energy and time upfront, and delayed our time-to-market, for something that never became a problem.

Worse yet, ORMs introduced their own problems and complexities and hindered development on an ongoing basis. It became a tax on the development team, and slowed down feature delivery for the foreseeable future.

For those that did have to do database migrations, ORMs didn’t make things much better. It was just another problem that you had to deal with, on top of everything else.

It’s painful to see history repeating itself, this time, at an even higher level that can impact the entire organization!

Also, as Nick Gottlieb pointed out in his excellent post, the true danger with lock-in with serverless, is with data lock-in. Unfortunately, this form of lock-in would impact your containerized services just as much!

Companies are finding that serverless teams are getting more done, and with fewer engineers. So, like a wise investor, the question we should be asking is: “Are the significant productivity returns worth the lock-in risk, which has a small chance of materializing into actual problems?”

Is the Future Serverless or Containers?

Serverless gives you a lot of productivity gains, at the expense of control over your infrastructure.

For a lot of our workflows—web APIs, stream processing, cron jobs, etc.—we don’t need all that control and it’s actually a blessing that someone else can take care of the plumbing for us.

But there will always be cases where we need to retain control of our infrastructure in order to optimize for performance, cost, or higher availability. Or perhaps our workload does not bode well with current limitations with serverless such as maximum execution time.

Instead of choosing one or the other, I believe serverless and containers should be used side by side. Indeed, many companies have found success with a hybrid approach.

- Use serverless for workloads where serverless meets their needs

- Use containers for where it doesn’t, for example, for workloads that:

- are long-running

- require more predictable performance

- require more resilience than can be easily achieved with serverless

- run at significant scale constantly, and the pay-per-invocation pricing model becomes too costly

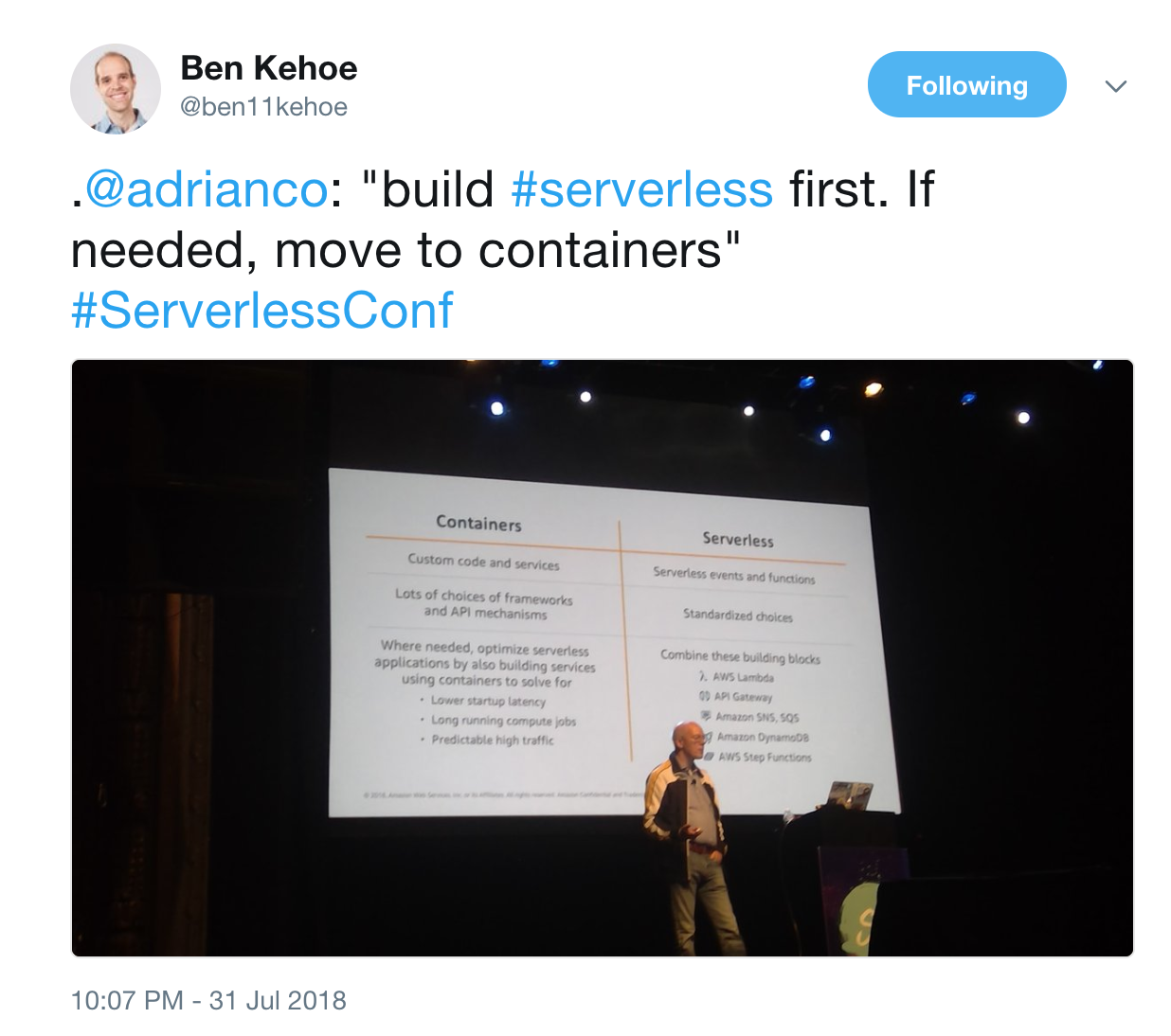

This is also the advice from none other than Adrian Cockcroft, former cloud architect at Netflix and currently VP of Cloud Strategy at AWS.

I believe we will eventually see a convergence of the two paradigms. Container technologies will eventually become serverless—think Fargate, plus per-invocation pricing model and millisecond billing. At the same time, serverless platforms would open up and allow you to bring your own containers. Advanced users would be able to retain some control of their infrastructure by providing API-compliant subcomponents for logging, etc.

And with the line between containers and serverless finally broken down, we can finally do away with the factions and stop talking about the underlying technologies. All I want to talk about is how to build products that my customers want to use, and how I can build them faster.

Let’s talk about that!